* Extinct has been quiet lately, as I work furiously to finish my book. Hopefully the pace of things will pick up a bit in the new year (so, ya know, stay tuned). “Problematica” is written by Max Dresow…

Ages ago, I wrote a post on the problem of classifying the enigmatic macrofossils of the Ediacaran biota. I promised a follow-up, which I wrote (and published)— but nothing ever made its way to Extinct. Then I wrote an even longer post on the problematic fossils of the Burgess Shale: especially, Opabinia regalis. And again I promised a follow-up, in which I would compare the case of the Burgess Shale to that of the Ediacaran biota. But then, nothing.

Well, I'm here to put things right.

This post will do double-duty, and will serve as Part II for both of these pieces. As such, it has two major tasks. The first is to explain how paleontologists have begun to generate positive evidence that Ediacaran macrofossils were the remains of animals, despite the basic epistemic predicament that has always dogged Ediacaran paleontology. The second is to say why the histories of Cambrian and Ediacaran paleontology have been so different. Why have the methods and concepts that cut so much ice in the Cambrian— like phylogenetic analysis— cut so little in the Ediacaran?

Let me begin by restating the basic problem with interpreting problematic fossils. To place a fossil on the tree of life, it is first necessary to make sense of its morphology— to identify a structure as this or that. Yet this requires a hypothesis of grouping at some level; and with problematica the choice of hypothesis is underdetermined. Ediacaran fossils are especially tricky in this regard, since, on the one hand, many features seem not to have been preserved, and on the other, those features that were preserved fail to disclose affinity even with large groups like the eumetazoans. So it is by no means clear what paleontologists should do when seeking to resolve the affinities of Ediacaran organisms.

Iconic Ediacaran fossils, including Spriggina (top left), Kimberella (left center), Avalofractus (bottom [far] left), Aspidella (bottom [center] left), Charnia (center), Dickinonia (top right), and Parvancorina (bottom right)

Faced with this quandary, the most obvious strategy is to seek out new material in hopes that it will disclose previously unobserved bits of anatomy. That was the strategy that established the bilaterian nature of Kimberella— an animal that was once interpreted as a jellyfish (and so, not a bilaterian). The jellyfish interpretation went mostly unchallenged for several decades after it was proposed in the 1960s. Yet it was based on scant material, and when a wealth of new specimens was discovered near the White Sea in Russia, it became evident that the organism was bilaterally symmetrical (Fedonkin and Waggoner 1997). That meant that it was probably a eumetazoan (although, beyond this, it is difficult to place, and some even dispute the eumetazoan placement).*

[* Here is a bonus example of this strategy at work, this one from the Burgess Shale. The animal called Hallucigenia was famously reconstructed as a “weird wonder” not allied to any known phylum— a worm provided with spike-like legs and a row of tentacles growing from its back. Yet when the holotype specimen was re-prepared, it was revealed that the row of dorsal “tentacles” was, in fact, a row of paired lobopodous limbs (Ramsköld, 1992). The animal had been reconstructed upside-down. Restored to the proper orientation, it was revealed to be a stem arthropod.]

Kimberella, though, is the exception, not the rule. In most cases, this wait-and-see strategy has resolved nothing at all. As such, recent work on the Ediacaran biota has tended to involve strategies that depart from an emphasis on static morphology. The next part of this post describes three of these strategies. Together they represent new lines of attack on the Ediacaran enigma, and ones that have begun to generate positive evidence that some Ediacaran organisms were indeed metazoans.

Strategy 1: The trace fossil approach

The first strategy might be termed the trace fossil approach. It works by mobilizing the trace fossil record (the record of trails, tracks, and burrows, interpreted as “traces” of past organismal activity) to constrain hypotheses of evolutionary relatedness. It involves two steps. First, researchers seek to establish causal links between traces and activities or structures. (They ask: what kind of activity or structure is likely to have produced that trace?) Then they make inferences about the phylogenetic affinity of trace-makers based on knowledge of the phylogenetic distribution of activities and structures. Consider: if a trace can be confidently linked to an activity or structure, and if that activity or structure is known only in bilaterians, then there is reason to suspect that the trace-maker was a bilaterian.

Generally speaking, it is difficult to figure out which organisms were responsible for producing which traces. Often it is impossible, beyond speculating, for instance, that the squiggle in the sediment was made by some kind of worm. Still, there are cases in which trace fossils are found on the same bedding plane as their ostensible producers, and these hold out the promise of establishing causal links between traces and their makers. Kimberella, for example, has sometimes been observed in association with the ichnofossil Kimberichnus (formerly Radulichnus), consisting of fan-shaped arrays of paired ridges (Fedonkin 2003). Now, Kimberichnus is included in the Radulichnus guild, so named because the marks resemble those produced by the action of a radula. And radulas have a phylogenetic distribution limited to mollusks. So, the inference goes, Kimberella may have been related to mollusks.

The association of Kimberella body fossils with the trace fossil Radulichnus, so named because it resembled the rasping marks made by a molluscan radula

To take a second case, imprints of the modular fossil Dickinsonia have been found in overlapping series, sometimes terminating in an apparent body fossil (Ivantsov & Malakhovskaya 2002). This has led a number of researchers to conclude that Dickinsonia was motile, and that it fed by grazing on microbial mats (Gehling et al. 2005; Sperling and Vinther 2010). The inference must defeat the alternative interpretation that the “footprints” were produced by physical currents, alternately lifting the passive organism and depositing it in the sediment (Evans et al., 2015). However, if Dickinsonia was actually motile, this would seem to rule out affinities with fungi, lichens, and algae, while supporting an animal placement.

A Dickinsonia body fossil (left) at the end of an overlying series of body impressions

The trace fossil approach is the oldest of the three approaches I will discuss, and the least probative. But the approaches are not mutually exclusive. Proposed animal affinities for Kimberella and Dickinsonia need not rest on trace fossils alone, and in recent years supporting evidence has come from a perhaps unexpected source: molecules.

Strategy 2: The biomarker approach

The second approach departs from an emphasis on morphology altogether. Instead, it focuses on the molecular composition of fossils: the biomarker approach. Here the idea is to locate diagnostic traits that are not anatomical structures or behavioral traces, but biomolecules with restricted phylogenetic distributions. Exemplary are the cholesterols, which are found almost exclusively in animals. And, it turns out, in dickinsonids from the White Sea region of Russia (Bobrovskiy et al., 2018).

By analyzing thin layers of organic matter associated with dickinsonids, Ilya Bobrovskiy and colleagues have shown that samples have a monoaromatic steroid distribution of about 93% cholesteroids, as compared to 10–12% in the enclosing sediments. This has led them to conclude that “molecular fossils”

firmly place dickinsoniids within the animal kingdom, establishing Dickinsonia as the oldest confirmed macroscopic animals in the fossil record (558 million years ago) next to marginally younger Kimberella from Zimnie Gory (555 million years ago). However alien they looked, the presence of large dickinsoniid animals, reaching 1.4 m in size, reveals that the appearance of the Ediacara biota in the fossil record is not an independent experiment in large body size but indeed a prelude to the Cambrian explosion of animal life. (Bobrovskiy et al. 2018, 1248)

More recently, Bobrovskiy and colleagues have examined Ediacaran fossils with putative digestive systems. These include White Coast Kimberella specimens, whose “guts” include “a notable depletion in the relative concentration of C-27 sterols in comparison to microbial mats” (Bobrovskiy et al. 2022, 5386). The depletion is interesting because only one “known natural process… can selectively remove C-27 sterol from a sterol mixture”— that is, “adsorption in the digestive system of invertebrates.” So, the inference goes, Kimberella probably had guts capable of adsorption, and this means it was an animal.

At the time of writing the biomarker approach has seen only limited application. There simply aren’t that many obvious places to apply it. Yet as Roger Summons and Douglas Erwin have observed, ancient molecules may provide “our best hope for unraveling the early history of animals and the affinities of the Ediacara biota,” especially if these molecules “allow us to differentiate specific metazoan clades, particularly among the bilaterians” (Summons and Erwin 2018, 1199). Best, but not only. There is one more strategy to discuss, which operates independently of evidence from molecular fossils.

Strategy 3: The developmental approach

The third strategy searches for diagnostic characters not in trace fossils or biomarker composition, but in developmental patterns. Call it the developmental approach. Here the idea is to use “ontogenetic” or “developmentally controlled characters” to constrain hypotheses of relationship with living groups. In other words: in the developmental approach, the phylogenetic signal comes from conserved developmental processes that are inferred to have been present in extinct taxa.

Consider recent work on Charnia masoni (Dunn et al. 2021). Charnia is a frondose Ediacaran fossil, which has been variously interpreted as a macroalgae, a sea pen, a marine fungus, and a “vendobiont” (Ford, 1958; Glaessner and Wade, 1966; Peterson et al., 2003). It is an iconic fossil— a member of the rangeomorphs, which are “among the oldest and most enigmatic components of the Ediacaran macrobiota” (Dunn et al. 2021, 1). Yet in the absence of clear homologies its phylogenetic affinities have been difficult to pin down.

Charnia, artwork by Marko Georgievski

Enter development. Now, it might seem odd to talk about development in an extinct organism, at least in the absence of structures like shells that preserve records of accretionary growth. However, in modular taxa, it is sometimes possible to reconstruct fossil growth series and to use these to infer developmental processes (Antcliffe and Brasier 2008). That is the case in Charnia. Yet before any inferences about development can be made, it is necessary to have a careful study of the creature’s anatomy.

To better characterize Charnia’s anatomy, Frances Dunn and colleagues performed x-ray and computed tomography on five specimens from the White Sea region (Dunn et al. 2021).* This revealed that the Charnia frond was composed of equally scaled, self-similar units ultimately derived from a single “branch” as opposed to a central stalk. The primary repeating unit they termed a first-order branch; and this was composed of second-order branches bound together medially, with third- and fourth-order branches derived from the basal margins of second-order branches (see the diagram). Altogether, these branches filled the breadth of the frond, and were probably internally connected, forming a series of fluid-filled cavities— shades of Seilacher’s vendobionts.

[* Computed tomography (CT) is a method of imaging that allows researchers to nondestructively characterize the entire three-dimensional volume of a fossil. It is now widely used in paleontology for a variety of applications (Racicot 2016).]

From these observations, Dunn and colleagues constructed a model of morphogenesis in Charnia, according to which new first-order branches were derived from second-order branches of the preceding first-order branch. The size of any branch was “dictated by the position of the first-order branch that precede[d] it in sequence along the apical-basal axis” (Dunn et al. 2021, 6). In addition, the organism was inferred to have exhibited “a shift in the primary developmental mode, from the differentiation of first-order branches to inflation of pre-existing first-order branches,” during its life cycle. “[The] shift was gradual and polarized along the principal frond axis, such that the outline shape of fronds [was] both regular and predictable, rather than exhibiting abrupt changes.” So, whether first-order branches were differentiating or inflating, the frond cut much the same figure in the water column.

Dunn et al.’s growth model for Charnia masoni, with a first-order branch (orange) traced through the illustrated growth permutations. Differently colored second-order branches illustrate that new first order branches tend to arise from a particular second-order branch (in this case, the fourth in sequence). At the bottom of the figure, a shift in developmental mode from differentiation to inflation is indicated

What does this tell us about where Charnia belongs on the tree of life? According to the authors:

C. masoni maintains differentiation of elements with concurrent axially delineated inflation, exhibits evidence for transitions in the primary developmental mode,… and the form of the organism is regular and predictable. This combination of characters is only otherwise seen within the Metazoa. Algae do not display a conserved form and fungal fruiting bodies do not display the maintained differentiation of new elements. Therefore… we conclude that there is no justification for considering an affinity for Charnia outside the animal total group. (Dunn et al. 2021, 7, emphases added)

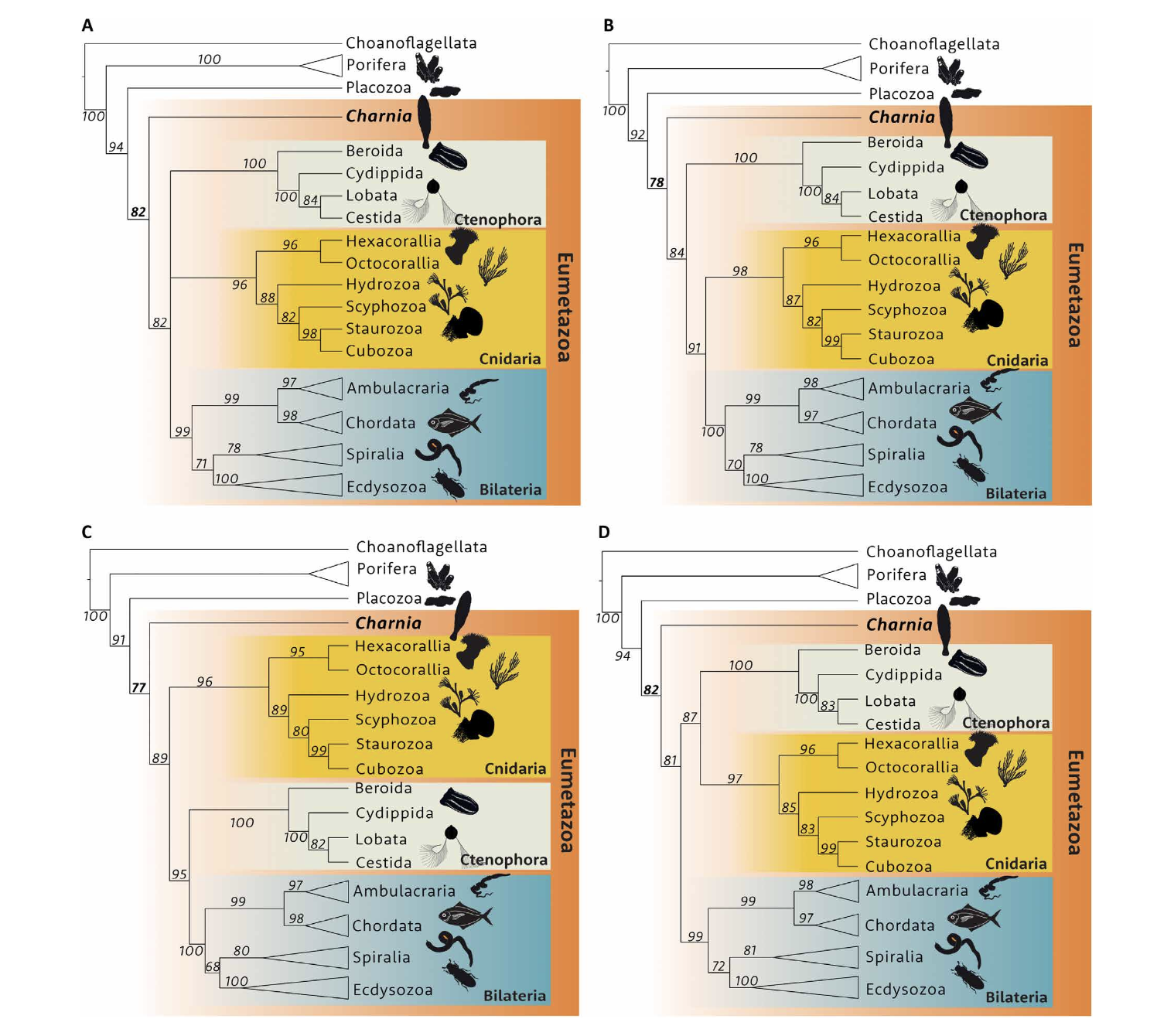

To solidify the assessment, Dunn and colleagues performed a Bayesian cladistic analysis on a dataset comprising 178 characters. (They were able to score 80 of these characters in Charnia.) This resolved C. masoni as a stem eumetazoan with 82% support, a result that was robust across several competing hypotheses about the relationship of cnidarians, ctenophors and bilaterians. So, Charnia was probably a eumetazoan.

Phylogenetic analyses, performed by Dunn et al., which recover a stem eumetazoan position for Charnia under a variety of topological constraints (i.e., hypotheses about the relationship of Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Bilateria)

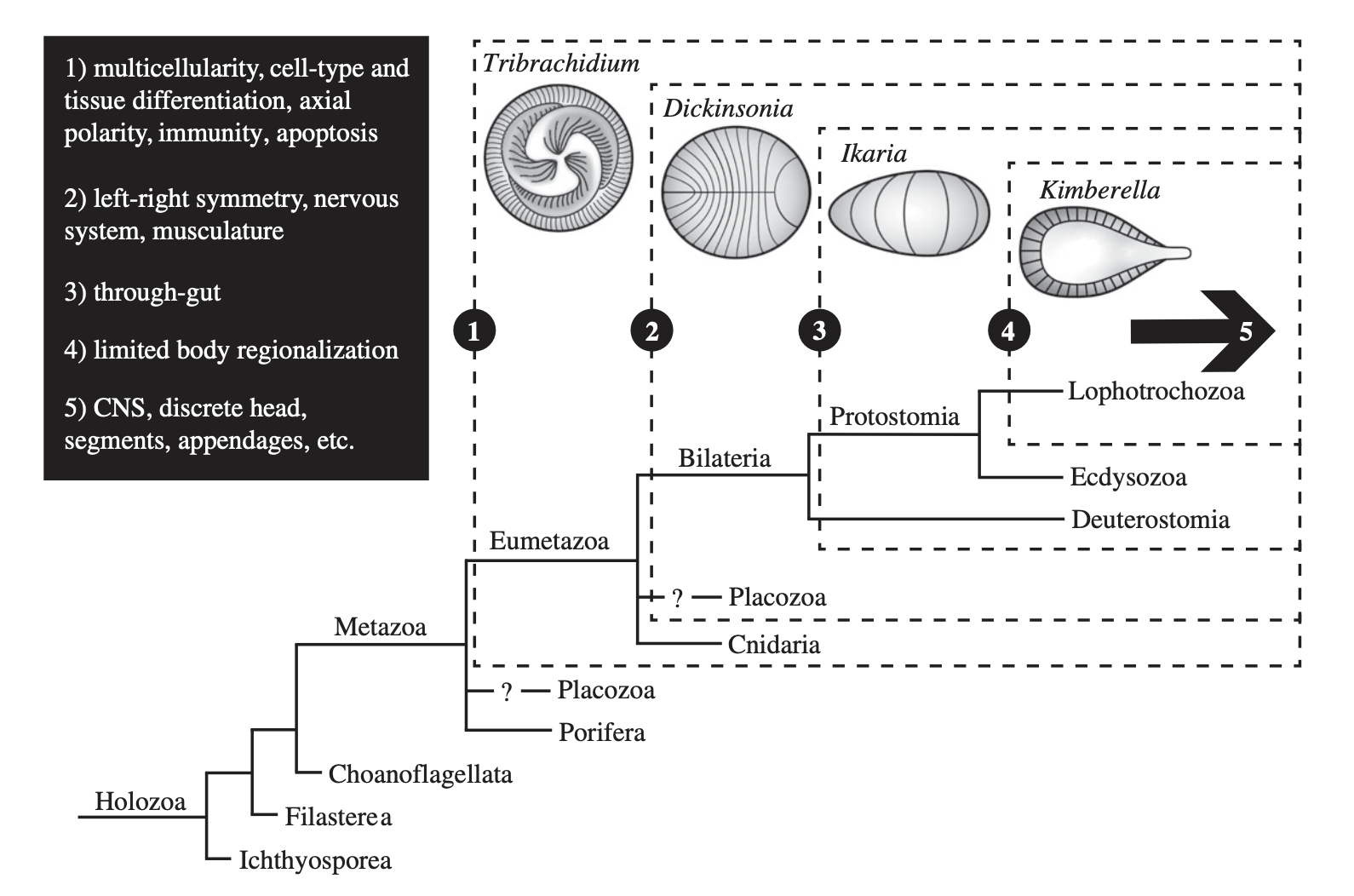

This is not the only study that has attempted to leverage development to decipher Ediacaran phylogeny. In a recent article, Scott Evans and colleagues have canvased the Ediacaran biota for characters controlled by conserved developmental processes (Evans et al. 2021). They make two big assumptions. The first is that the fossils under consideration are metazoans. The second is that developmental capacities can be inferred from fossil evidence. The assumptions are non-trivial. But grant them, and they will constrain Tribrachidium to the eumetazoans, Dickinsonia to the bilaterians, and Kimberella to the lophotrochozoans.

A figure from Evans et al. (2021), with original caption: “Holozoan phylogeny with inferred placement of representative White Sea taxa (dashed boxes) based on developmentally relevant characters (1–5, black box). Characters represent those that can be identified based on morphological expression in representative Ediacara fossils, and thus are not indicative of their earliest appearance. Arrow represents increased combinatorial complexity of transcription factor interactions in all three groups of bilaterians. Question marks represent uncertainty of placozoan placement. Ctenophores omitted to avoid uncertainty. CNS, central nervous system”

Ontogeny does not recapitulate phylogeny, but it may yet illuminate it.

Burgess beasties and Ediacaran enigmas

In “Ediacaran enigma,” I asked why it is the case that the Ediacaran soft-bodied fossils have so stubbornly resisted taxonomic placement. Here is what I said:

To begin, most Ediacaran fossils are preserved as casts and molds in relatively coarse sediment, and this has led to a considerable loss of anatomic detail. An especial problem is the absence of readily identifiable anatomical features, which is partly a function of information loss and partly a matter of evolution. Ediacaran fossils are ancient, nestled deep in the evolutionary tree of animals (assuming they are indeed animals). This means they did not possess many of the features characteristic of living groups, including those traits that define the basal nodes of surviving clades. But then how should they be classified?

Still, it may not be evident why this constellation of factors has made deciphering Ediacaran problematica in particular such an acute challenge. In this final section I take up the matter again, utilizing as my method a historical comparison.

There have been many problematic fossils in the history of paleontology, and many of these are problematica no longer. This includes members of the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale fauna, which were once at the heart of heated discussions in paleontology and evolutionary theory (Brysse 2008). Writing in 1989, Alberto Simonetta and Simon Conway Morris described problematica as “one of the most intriguing, and most ignored, of the problems in biology” (Simonetta and Conway Morris 1989, ix). The very same year, Stephen Jay Gould’s Wonderful Life brought the animals of the Burgess Shale to the attention of a general audience. In Gould’s hands, creatures like Hallucigenia took on almost metaphysical significance, compelling entirely new views of evolution. Today, though, problematica rarely excite the same passions or elicit the same statements of scientific (and philosophical) importance. Why are problematica no longer the urgent scientific problem they once were? The short answer is that many problematic fossils are not as problematic as they used to be. Consider, for example, the “weird wonders” of the Burgess Shale (Gould 1989).

A reconstruction of the Burgess Shale fauna, by Carel Brest van Kempen. Opabinia (the subject of my earlier post) is pictured in the middle-right of the frame, executing a somersault to capture a swimming worm

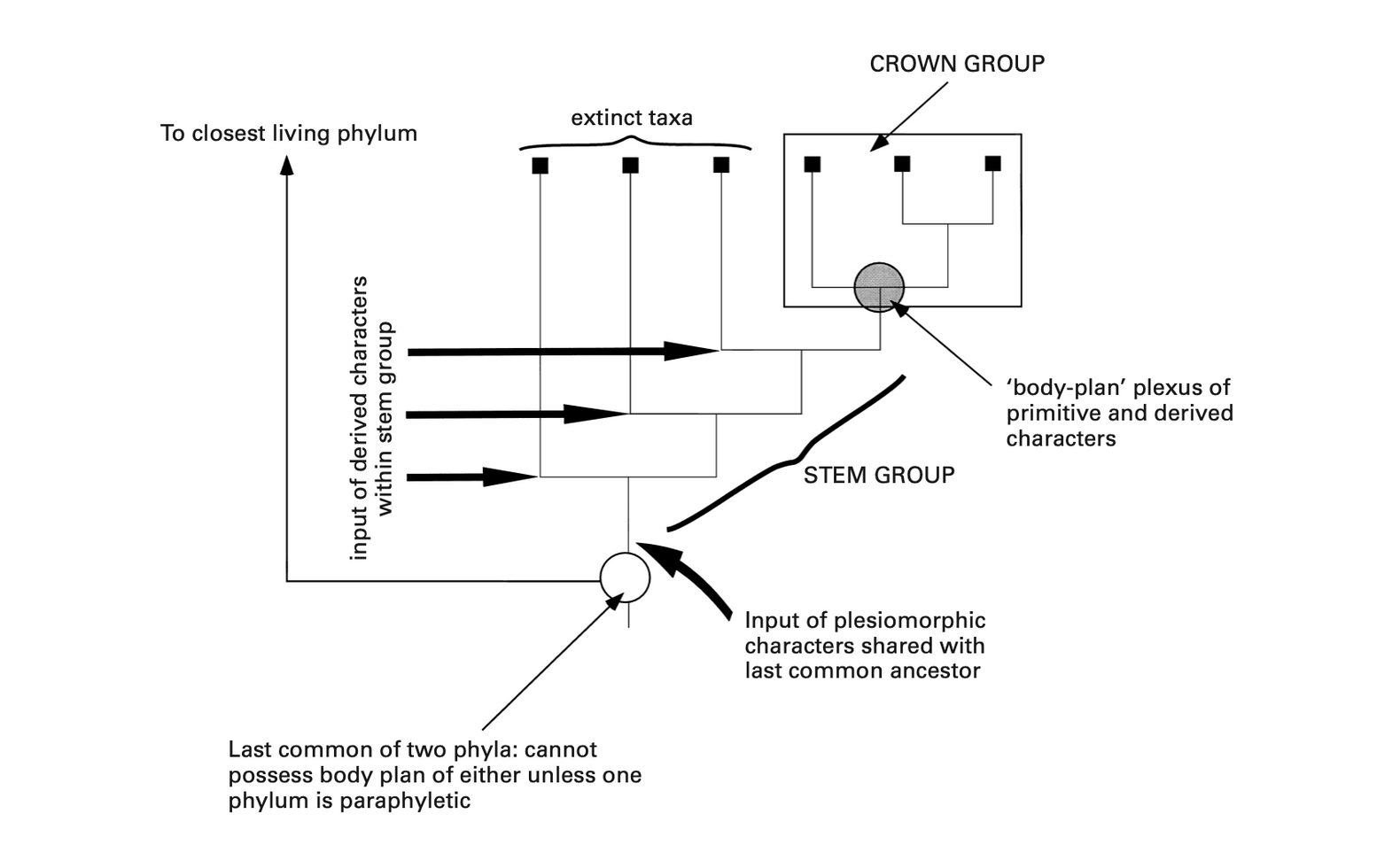

In an excellent paper, Keynyn Brysse has described “the second reclassification of the Burgess Shale fauna,” which began with early cladistic analyses of Burgess arthropods, and gathered steam with new work on oddballs like Hallucigenia and Opabinia (Brysse 2008). As Brysse writes, “The adoption of cladistic methodology and its corollary stem group concept provided an entirely new taxonomic framework within which to situate these bizarre and seemingly unique forms” (311). It was successful, at least in part, because it allowed paleontologists to avoid a devil’s choice. Previously, when a problematic fossil came under a paleontologist’s microscope, the paleontologist could do one of two things. The first was to include it in the least dissimilar living group— a procedure that involved changing the definition of that group to accommodate the troublesome fossil. The other was to erect an entirely new taxonomic category to house the oddball— even a new phylum-level category, if the creature’s morphology was strange enough.

Since many Burgess fossils both lacked diagnostic features of living groups and possessed strange characters of their own, a popular strategy was to regard them as representatives of extinct class- or phylum-level groups: failed evolutionary experiments. That was the strategy Gould favored in Wonderful Life, and it led to some of the book’s most eye-catching claims. Yet it was never a popular solution. Martin Glaessner, to name a prominent critic, argued that “failures are not phyla”— the phylum is a success category, and extinct taxa with one or a few members are not evolutionary successes (Glaessner 1984, 135). He thus favored the first strategy; but in response, others alleged that this ran the risk of seriously distorting our picture of metazoan evolution (e.g., Bengtson 1986).

This is where the stem group concept did its work. In effect, it offered a third way to deal with fossils that both lacked features diagnostic of living groups and possessed features all their own. That is, a paleontologist could locate such creatures on the stem of a living clade, including but not limited to those clades designated as phyla. Extinct basal taxa are not expected to possess all the diagnostic features of living groups. What’s more, they’re expected to possess features absent in living groups. Anyway, there’s no need to erect a new class or phylum to accommodate Opabinia and its strange clawed proboscis. The creature was simply a stem arthropod despite its morphological peculiarities (Budd 1995). Problem (apparently) solved. This is the story of the Burgess Shale fauna in a nutshell. It’s a story of success. Although questions remain, many of the most confounding members of the fauna have found homes on the stems of living clades. Opabinia and Anomalocaris were stem arthropods. Hallucigenia was a stem onychophoran. And so on.

A representation of stem and crown groups, from Budd and Jensen (2000)

Why has the history of Ediacaran paleontology been so different? Simply put, the challenge is different. The problem with the Burgess Shale fauna— the thing that tempted researchers to recognize new classes and phyla among the oddities— was their morphological distinctiveness. As Gould put it, “the animals seem… so damned curious, [and] different from [surviving] lineages” (Gould 1991, 414). But that isn’t the case with Ediacaran fossils. The problem with these fossils isn’t that they possess unique morphological characters that seem to warrant the erection of new phylum-level groups to accommodate their uniqueness. It’s rather that they possess so few characters that might link them to living clades. Unlike Burgess forms, many Ediacaran fossils defy close comparison with extant organisms. Even Kimberella, a probable bilaterian, possesses no morphological character apart from bilateral symmetry “that could identify [it] as a mollusc or even a bilaterian animal” (Runnegar 2021, 14).

The difference matters. In the Burgess case, researchers could perform a phylogenetic analysis and— armed with the stem group concept— place problematic taxa on the stems of living clades. However, in Ediacaran paleontology, the absence of demonstrable homologies between living and extinct forms has made even phylogenetic analysis fraught with difficulty (Dunn et al. 2021). Presumably most Ediacaran forms belong on the stem of one clade or another. But in the absence of demonstrable homologies it is difficult to say which clades these are.

So the Ediacaran enigma has endured even as many of the “weird wonders” of the Burgess Shale have found homes on the tree of life. It’s simply a different challenge, and one that cannot be solved by a relatively straightforward application of phylogenetic analysis. The situation is not hopeless, especially since multiple innovative strategies now exist for constraining the phylogenetic affinities of Ediacaran fossils. Yet it remains to be seen whether these are up to the challenge, or whether a resolution to the Ediacaran enigma must await a more powerful strategy for overcoming stubborn underdetermination.

References

Bengtson, S. (1986). The problem of the problematica. In A. Hoffman, & M. H. Nitecki (Eds.), Problematic fossil taxa (pp. 3–11). Oxford University Press.

Bobrovskiy, I., Hope, J. M., Ivantsov, A., Nettersheim, B. J., Hallmann, C., & Brocks, J. J. (2018). Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals. Science, 361, 1246–1249.

Bobrovskiy, I., Nagovitsyn, A., Hope, J. M., Luzhnaya, E., & Brocks, J. J. (2022). Guts, gut contents, and feeding strategies of Ediacaran animals. Current Biology, 32, 5382–5389.

Brysse, K. (2008). From weird wonders to stem lineages: The second reclassification of The Burgess shale fauna. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 39, 298–313.

Budd, G. E. (1995). The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group. Lethaia, 29, 1–14.

Dunn, F. S., & Liu, A. G. (2017). Fossil focus: The Ediacara biota. Paleontology, 7. www.palaeontologyonline.com/articles/2017/fossil-focus-ediacaran-biota/

Dunn, F. S., Liu, A. G., & Donoghue, P. C. J. (2018). Ediacaran developmental biology. Biological Reviews, 93, 914–932.

Dunn, F. S., Liu, A. G., Grazhdankin, D. V., Vixsebose, P., Flannery-Sutherland, J., Green, E., Harris, S., Wilby, P. R., & Donoghue, P. C. J. (2021). The developmental biology of Charnia and the eumetazoan affinity of the Ediacaran rangeomorphs. Science Advances, 7, eabe0291.

Evans, S. D., Droser, M. L., & Gehling, J. G. (2015). Dickinsonia liftoff: Evidence of current derived morphologies. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 434, 28–33.

Evans, S. D., Droser, M. L., & Erwin, D. H. (2021). Developmental processes in Ediacara macrofossils. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 28820203055. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.3055.

Fedonkin, M. A. (2003). Origin of the metazoa in the light of proterozoic fossil records. Palaeontological Research, 7, 9–41.

Fedonkin, M. A., & Waggoner, B. M. (1997). The late precambrian fossil Kimberella is a mollusc-like bilaterian organism. Nature, 388, 868–871.

Ford, T. E. (1958). Precambrian fossils from Charnwood Forest. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society, 31, 211–217.

Glaessner, M. F. (1984). The dawn of animal life. A biohistorical study. Cambridge University Press.

Glaessner, M. F., & Wade, M. (1966). The late precambrian fossils from Ediacara, South Australia. Palaeontology, 9, 97–103.

Gould, S. J. (1989). Wonderful life: The Burgess shale and the meaning of history. W. W. Norton & Co.

Gould, S. J. (1991). The disparity of the Burgess shale arthropod fauna and the limits of cladistic analysis: Why we must strive to quantify morphospace. Paleobiology, 17, 411–423.

Ivantsov, A. Y., & Malakhovskaya, Y. E. (2002). Giant traces of vendian animals. Doklady Earth Sciences, 385, 618–622.

Peterson, K. J., Waggoner, B., & Hagadorn, J. W. (2003). A fungal analog for Newfoundland Ediacaran fossils? Integrative and Comparative Biology, 43, 127–136.

Racicot, R. (2016). Fossil secrets revealed: CT scanning and applications in paleontology. The Paleontological Society Papers, 22, 21–38.

Ramsköld, L. (1992). The second leg row of hallucigenia discovered. Lethaia, 25, 221–224.

Runnegar, B. (2021). Following the logic behind biological interpretations of the Ediacaran biota. Geological Magazine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756821000443

Simonetta, A. M., & Conway-Morris, S. (1989). The early evolution of metazoa and the significance of problematic taxa. Cambridge University Press.

Sperling, E. A., & Vinther, J. (2010) A placozoan affinity for Dickinsonia and the evolution of late proterozoic metazoan feeding mode. Evolution & Development, 12, 201–209.

Summons, R. E., & Erwin, D. E. (2018). Chemical clues to the earliest animal fossils. Science, 361, 1198–1199.