* This is the fortieth installment of this little essay series, “Problematica.” I wanted to do something special to mark the occasion— writing forty of these things was no small amount of work, and like everyone else, I’m fond of even numbers. So I decided to do something I’ve been putting off, which is to write about a favorite author of mine, Richard Fortey. (By the way— I swear this is true— I didn’t realize that there was a forty/Fortey thing going on until after I began writing this. No, really!)

I’ve long been interested in two things: writing and the nitty-gritty of geology and paleontology. No one brings these things together more seamlessly than Richard Fortey. His death is a great loss— I, for one, had hoped to meet him, and perhaps even to interview him for the book I’m writing. But I will continue to cherish his books, which are without peer as tokens of exceptional craftsmanship: concise, rhythmic, and erudite, always able to find the right metaphor, the deft allusion, the unexpected word. The dear man, I miss him already.

“Problematica” is written by Max Dresow…

Many people believe— rightly, in my opinion— that John McPhee is the master prose stylist of the earth sciences. He is the successor, not of the celebrated John Playfair, but of his countryman Hugh Miller, who wrote some of the finest sentences ever to appear in the geological literature. Here, for example, is Miller, stirred to reverence by the discovery of an unconformity at Oban:

There are no sermons that seem stranger or more impressive to one who has acquired just a little of the language in which they are preached, than those which, according to the poet, are to be found in stones: a bit of fractured slate, embedded among a mass of rounded pebbles, proves voluble with ideas of a kind almost too large for the mind of man to grasp. The eternity that hath passed is an ocean without a further shore, and a finite conception may in vain attempt to span it over. But from the beach, strewed with wrecks, on which we stand to contemplate it, we see far out towards the cloudy horizon many a dim islet and many a pinnacled rock, the sepulchres of successive eras,— the monuments of consecutive creations… and— as in a sea-scene in nature, in which headland stretches dim and blue beyond headland, and islet beyond islet, the distance seems not lessened, but increased, by the crowded objects— we borrow a larger, not a smaller idea of the distant eternity, from the vastness of the measured periods that occur between.

And now hear John McPhee, describing his experience as an undergraduate student of geology in the 1950s:

I used to sit in class and listen to the terms come floating down the room like paper airplanes. Geology was called a descriptive science, and with its pitted outwash plains and drowned rivers, its hanging tributaries and starved coastlines, it was nothing if not descriptive. It was a fountain of metaphor— of isostatic adjustments and degraded channels, of angular unconformities and shifting divides, of rootless mountains and bitter lakes. Streams eroded headward, digging from two sides into mountain or hill, avidly struggling toward each other until the divide between them broke down, and the two rivers that did the breaking now became confluent… Stream capture… There seemed indeed to be more than a little of the humanities in this subject. Geologists communicated in English; and they could name things in a manner that sent shivers through the bones. They had roof pendants in their discordant batholiths, mosaic conglomerates in desert pavement. There was ultrabasic, deep-ocean, mottled green-and-black rock— or serpentine. There was the slip face of the barchan dune… There were festooned crossbeds and limestone sinks, pillow laves and petrified trees, incised meanders, and defeated streams… Pulsating glaciers. Hogbacks. Radiolarian ooze. There was almost enough resonance in some terms to stir the adolescent groin. The swelling up of mountains was described as an orogeny. Ontogeny, phylogeny, orogeny— accent syllable two.

Neither of these passages has left my head since I read them. They’re almost too good, especially McPhee’s cockeyed ode to the language of descriptive geology. (Seriously. No one writes like this. And if you can embrace the long-winded style, Miller’s prose is just as good.) Yet when I think of “sticky” sentences— sentences that instantly inscribe themselves on the long-term memory— I think of someone else, who is perhaps the only recent writer who deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as John McPhee. That is Richard Fortey.

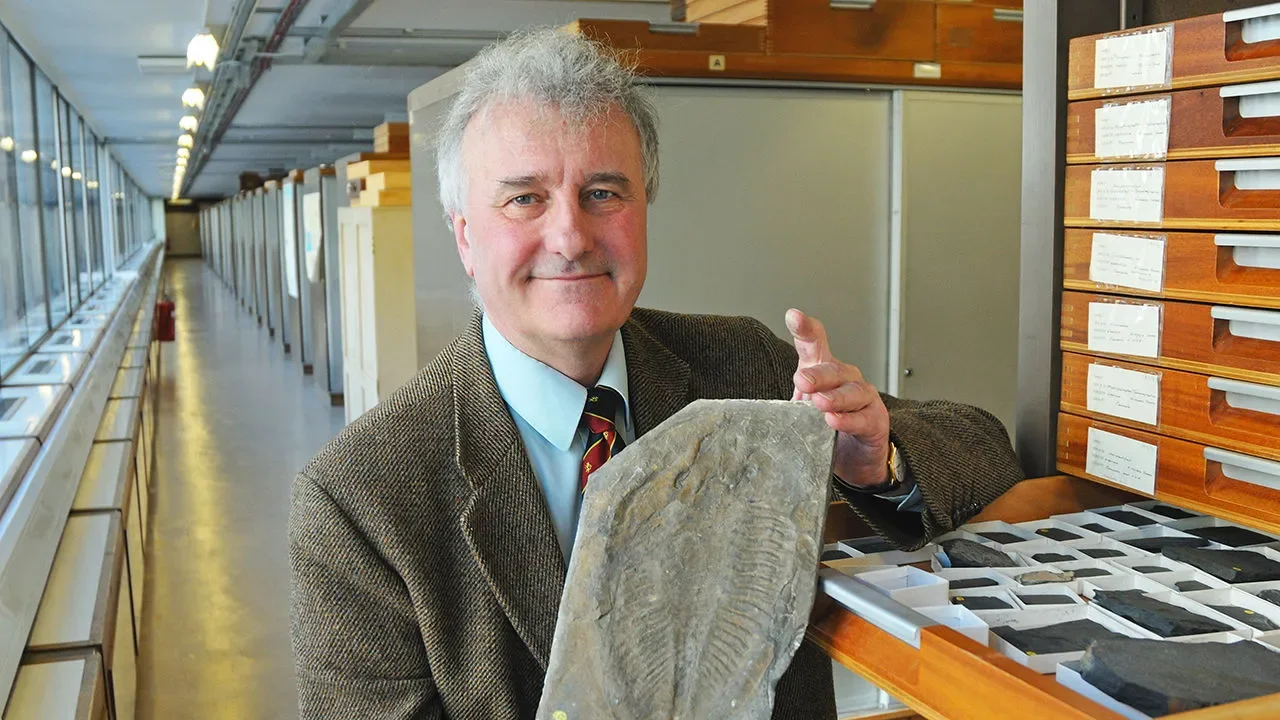

Richard Fortey died this past May. For those who don’t know, he was a British paleontologist and geologist with an interest in the Ordovician Period and an affinity for trilobites. He was also an accomplished naturalist, a television presenter, and even a novelist, having written several humorous novels under pseudonyms early in his career. Many good obituaries have been written, so I won’t attempt to write one myself. Instead, I want to commemorate my favorite geological writer in a way that I think he would have appreciated. I want to share some of my favorite Fortey-an sentences.

The list is, admittedly, pretty arbitrary. Each of Fortey’s books drips with the incisive, the graceful, and the snort-inducing. (Fortey on fern fronds: “They unwind like those honking party tooters blown by irritating guests.”) Anyway, please understand— I’m not trying to produce a definitive ranking of Fortey’s best sentences or something like that. I’m merely trying to assemble some fragments that exemplify his gifts as a writer. As such, I’m going to confine myself to the three books I like best, Earth: An Intimate History, Life: An Unauthorized Biography, and Trilobite: Eyewitness to Evolution.

The passages are presented in no particular order, and with minimal commentary. I hope they’ll stick in your head, too.

* * *

Every one of Richard Fortey’s books begins on a high note. He must have spent a huge amount of time crafting these paragraphs; all of them are memorable, intimate, tangled (in that special Fortey-an way), and, frankly, brilliant. My favorite is the opening of Earth, his book about “the way in which plate tectonics has changed our perception of the earth.” Here is just some of it, starting at the top:

It should be difficult to lose a mountain, but it happens all the time around the Bay of Naples. Mount Vesuvius slips in and out of view, sometimes looming, at other times barely visible above the lemon groves. In parts of Naples, all you see are lines of washing draped from the balconies of peeling tenements or hastily constructed apartment blocks: the mountain has apparently vanished. You can understand how it might be possible to live life in that city only half aware of the volcano on whose slopes your home is constructed, and whose whim might control your continued existence.

As you drive eastwards from the centre of the city, the packed streets give way to a chaotic patchwork of anonymous buildings, small factories, and ugly housing on three or four flours. The road traffic is relentless. Yet between the buildings there are tended fields and shaded greenhouses. In early March the almonds are in flower, delicately pink, and there are washes of bright daffodils beneath the orchard trees; you can see women gathering them for market… Oranges and lemons are everywhere. Even the meanest corner will have one or two citrus trees, fenced in and padlocked against thieves. The lemons hang down heavily, as if they were too great a burden for the thin twigs that carry them. The soil is marvelously rich; with enough water, crops will grow and grow.

Vesuvius, from Naples

Now let me jump forward to exhibit something Fortey does really well.

Everything about Sorrento is rooted in the geology. The town itself is in a broad valley surrounded by limestone ranges, which flash white bluffs on the hillsides and reach the sea in nearly vertical cliffs— an incitement to dizziness for those brave enough to look straight down from them. Seen from a distance the roads that wind up the sides of the hills look like folded tagliatelle. Stacked blocks of the same limestone are used in the walls that underpin the terraces supporting the olive groves. In special places there are springs that spurt out fresh, cool water from underground caverns. These sources are often flanked by niches containing the statue of a saint, or of the Virgin: water is not taken for granted in these parts… The country backing the Bay of Naples is known as Campania, and the same name, Campanian, is applied to a subdivision of geological time belonging to the Cretaceous Period. If you look carefully on some of the weathered limestones, you will see the remains of seashells that were alive in the time of dinosaurs… A paleontologist can identify the individual fossil species and use them to calibrate the ages of the rocks, since the succession of species is a measure of geological time. The implication is clear enough: in Cretaceous times all these hilly regions were beneath a shallow, warm sea… Time and burial hardened the muds into the tough limestone we see today. They are sedimentary rocks, subsequently uplifted to become land; earth movements then tilted them— but this is to anticipate. What one can say is that the character of the limestone hills is a product of an ancient sea.

Notice what Fortey is doing here. He is introducing fundamental concepts like the geological time scale, the idea of fossils as time keepers, and the category of sedimentary rock, without resorting to the tactic of lesser writers— that is, clearing his throat and saying, “Geologists recognize three types of rocks: sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic…” Somehow it all tumbles out of a breezy tour of Sorrento.

Here’s a bit more of that tour, just for fun:

There is something different about the cliffs behind the harbour in the middle of Sorrento. From afar they have a greyish cast, a dull uniformity lacking all the brilliance of limestone. The streets career downwards towards the sea below the central piazza, following a steep-sided valley. Now you can see the rock in the valley sides. It is brownish, like spiced cake, and displays little obvious structure. Look closely and you see that, embedded within it, like dates in a home-bake, there are darker patches… This rock is called the Campanian Ignimbrite… An explosion of steam and gluey lava blew out a great hole in the earth at the edge of the Tyrrhenian Sea— not so much a bite out of Italy’s profile as a huge punch. A vast cloud of incandescent material buoyed up with gas flowed like a fiery tidal wave across the limestone terrain… Palaeolithic human witnesses to this destruction… must have thought the gods had gone berserk.

Earth is really good. It might be my favorite “popular science” book about geology— it is, at once, a splendid travel book, a wonderfully lucid account of the basics of plate tectonic theory, and a surprisingly nimble history of tectonic thinking, with a focus on Charles Lyell, Eduard Suess, and Arthur Holmes. The best chapter is the chapter on the Alps, which has more than the usual share of historical asides. Here we see Fortey at his descriptive best, all deft images and bouncy expressions. Consider some sentences. The Jura mountains “are like the wrinkles on the forehead of a very old man.” Deep, hot rocks creep beneath our feet “like a contrary glacier of the underworld.” The grey rocks of San Bernardino emerge from the ground “like a school of whales breaking the water.” The Gotthard Massif is “the heaviest kind of grey granitic gneiss, a rock of ancient and implacable solidity, grim and giving no quarter.”

It goes on. We read of the “spun complexity” of alpine strata, of their “perverse plications and ceaseless crenulations.” Deciphering the structure of the range, Fortey tells us, was “like unscrambling an omelette.” It sounds hard. Yet we know by this point in the chapter how the omelette was (mostly) unscrambled, and beyond that, how geologists managed to reconstruct at least some of the forces that contributed to scrambling it up. Imitating Suess (who “never thought other than globally”), Fortey’s synopsis lifts us into space:

In our mind’s eye we have to draw backwards from the particular spot…; or rather upwards, as if we were carried on a rocket into the ionosphere. Distance lends its own clarity… We can now appreciate the whole sweep of the Alps, and its continuation eastward into the great arc of the Carpathian Mountains… We can comprehend that this is all one interconnected system, and that our path through Switzerland was no more than an amble through one tiny piece of a great mountain chain, which in turn links other ranges all the way eastwards to the Himalayas. Then we see Africa: a vast continent, and an ancient one. We can appreciate its presence, its mass, its unyielding solidity… From this height, mountain ranges begin to seem more like wrinkles; nappes might be no more than tics on a spasm of the crust. If Africa is moving northward— and it is— it suddenly seems plausible that all those monstrous rocks and buckled limestones and squeezed gneisses… might be no more than the desperate scrambling of the earth away from the encroachment of the inescapable giant. The nappes fled northward; the whole Carpathian chain curves away from the oppressor. The ancient mass of northern Europe… braced itself against the onslaught, and the effects are felt beyond the Alps themselves. The basement rocks of Europe shivered, and the rocks that covered them were flexed. Even the shape of England is influenced today by the approach of the distant giant. Everything scales to the great event: the intimate history links with the grander design. You cannot look on too large a scale to help you understand a solitary footstep through the landscape, and single crystal on a cliff.

The Alps, from space

I have to be careful— this exercise is becoming even more arbitrary than I intended. I could just as well have highlighted a half-dozen other parts of Earth, like the stunning description of the geological structure and history of Newfoundland (and its tectonic twin, the Scottish Highlands), or the valedictory chapter, titled “World View.” But Fortey has written other books, too, and they all drip with beauties. Consider the opening of Life, which finds a teenage Fortey on a small boat bound for Svalbard.

Salterella dodged between the icebergs. While the small boat bucked and tossed, I hung over its side, peering down into the clear Arctic waters. I had not known that there could be such density of life. This frigid sea was a speckled mass of organisms. Tiny copepod crustaceans, looking like so many animated peas, beat their way in their thousands through the surface waters, feeding on plankton that I knew must be there, but which could not be seen without a microscope. There were jellyfish of every size: white, gently pulsing discs as delicate as spun glass; small pink barrage balloons decked with beating cilia, which appeared to be solid— but became gelatinous and impalpable if grasped from the water; an occasional orange monster with tentacles that promised evil stings for fish or mammal. They drifted in their millions, swirling and beating against the dumb tides, concealing purpose in contractions as instinctive as breathing, like protoplasmic lungs dilating and constricting in primitive obedience to the prompting of the currents.

Later in the same book, we follow the author to Oman, on the trail of ancient glaciers:

The whole valley opened up into a kind of natural amphitheatre, surrounded by steep cliffs evidently composed of [a] curious, medley rock. But the floor of the amphitheatre was another kind of substance altogether, a hard, solid rock, in complete contrast to the clay-and-boulders, which could now be seen to lie as a great blanket immediately on top of this floor. What was extraordinary was that this hard rock, too, had been polished and gouged, but on a colossal scale. The whole valley floor had been scraped: great grooves scoured the surface in a set of lines that ran virtually parallel from one side of the wadi to the other. Some of the grooves deepened, in places, as if they had been scraped by the fingernails of some Titan clawing the ground in rage.

And here he is offering a sociological aside, describing the “pecking order in science” with theoreticians at the top and “field scientists” at the bottom:

The most rarefied and clever scientists, sitting at the top of the hierarchy, are the theoretical physicists… Such great men cruise in abstract world where lesser souls seek the consolation of metaphor, or the mundane comfort of an analogy. Somewhere not far below them are experimentalists… These scientists translate the dreams of the theoreticians into experimental tests. In the past such experimental wizards might have been arcane figures like the aristocratic chemist Lavoisier squirreling away in the forgotten wing of some crumbling stately home, while the estate rotted and mad aunts raved in the east wing…

I can’t read the last sentence without smiling. It’s just so good.

Antoine Lavoisier’s actual estate

I am aware that this post is a mostly disconnected series of long-ish quotations, and I don’t want to overstay my welcome. Let me close, then, with a passage from Trilobite, which is a fitting tribute to the man, and I think, a rousing description of a life well-spent:

I have spent much of my working life remaking the world. I have pushed half of Europe across half an Atlantic. I have closed ancient seaways and opened up others. I have been able to name an ocean greater than the Mediterranean and then condemned it to perdition… When I meet some of my commuting acquaintances on the 6:21 home to Henley-on-Thames, they occasionally enquire what I have done that day. I have been know to reply: “I moved Africa 600 kilometers to the south.” They usually turn quickly to the football page.

Rest now, Richard Fortey.