Derek Turner writes . . .

A few weeks ago, the journal Nature published a paper arguing for a major revision of dinosaur phylogeny. You've probably seen it in the headlines. I’ll leave it to others to subject Matthew Baron, David Norman, and Paul Barrett’s phylogenetic analysis to careful scrutiny. (See this excellent piece by Darren Naish for some preliminary discussion.) But however things look when the dust settles, the paper has left me thinking a lot about dinosaur hips. And I have many questions, along with one modest philosophical argument to make.

The Old Picture

On the one hand, you have—or had?—your lizard-hipped (saurischian) dinosaurs. That group included all the big sauropods and their relatives, as well as the theropods. On the other hand, you have your bird-hipped (ornithischian) dinosaurs, including the iconic Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Ankylosaurus, as well as all the hadrosaurs. The basic skeletal difference between the two is easy to discern.

If you look closely at a skeleton of, say, an alligator, you can see the two pelvic bones called the ischium and the pubis. Although alligators aren't really lizards, they too have the reptilian "lizard hip" design. The bigger bone on top of the hip socket is the illium. The pubis kind of points forward and down, while the ischium sticks out behind. (As you can tell, I am not exactly a connoisseur here, but luckily, the morphology is so easy to perceive that even us philosophers can do alright. But see also Dave Hone's helpful discussion here.)

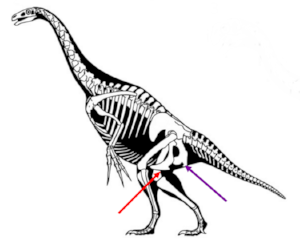

The skeleton of an alligator. The red arrow is pointing at the pubis, which is sticking forward, while the purple arrow indicates the ischium. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (though I added the arrows).

Now if you glance at the pelvis of a theropod dinosaur, or one of the big sauropods, they look sort of like the alligator pelvis, at least, in the sense that the pubis and ischium bones are pointing in different directions.

T. rex has a lizard-like hip joint, with the pubis (red arrow) pointing down and a bit forward, and the ischium (purple arrow) jutting backward. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (again, with the arrows added).

And here's Apatosaurus. Notice how the pubis (red) also juts forward, away from the ischium (purple). Image courtesy of wikimedia commons.

However, if you look at the skeleton of a modern bird, the hips look totally different. The ischium and the pubis bones are kind of smooshed together, with the pubis pointing backwards.

The skeleton of an emu. See how the pubis (red) and ischium (purple) both point backwards. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

The pelvis of a hadrosaur (one of the bird-hipped dinosaurs) looks more like the pelvis of a bird than like that of either a T. rex or an alligator. The pubis and the ischium bones are smooshed together and pointing aft.

A skeleton of Edmontosaurus. Note how the pubis (red) and the ischium (purple) are sort of smooshed together and pointing backwards.Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added). Also, in this dinosaur, there is a kind of bony flange sticking forward from the pelvic girdle, but that's a different structure, the anterior process, as Dave Hone explains here.

And for good measure, here's a Stegosaurus with the bird-hipped morphology. See how the pubis (red) and ischium (purple) are right up against each other. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

Until a few of weeks ago, the received view was that sometime back in the Triassic period, these two major branches of dinosaurs split off from one other and went their separate evolutionary ways.

The old dinosaur phylogeny that you probably learned as a kid.

But there was already something quite strange about this picture, even before Baron, Norman, and Barrett called it into serious question. We know that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs—that is, from lizard-hipped dinosaurs. So somewhere in there—probably in the evolutionary trajectory of small maniraptorans, which gave rise to birds—there was a major change in pelvic morphology.

Actually, the change from lizard hips to bird hips might have happened several times (even on the old picture): It may have happened independently in birds and dromaeosaurs (think of Deinonychus and Velociraptor). Those dromaeosaurs, weirdly, have pubis bones that point somewhat downward and backward, even though the shape of the pubis reminds one of T. rex.

This is Deinonychus--a weird case. It's a theropod, and so traditionally classified as saurischian, but the hip obviously looks kind of bird-like, with the pubis (red) pointing backwards and smoothed up against the ischium (purple). Compare it to the emu above. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

And then there are the enigmatic therizinosaurs—another theropod group that also acquired a more bird-like hip construction. Why did these changes occur?

Another weird case. This is a reconstruction of a therizinosaur.. Therizinosaurs were theropods, hence saurischians (on the old picture), and yet they too seem to have had the pubis (red) smooshed up against the ischium (purple). Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

Another question: What sort of hips did dinosaurs start out with? Did they start out with lizard-like hips, or bird-like hips? Suppose, as seems likely, that they started out with lizard-like hips. That would mean that the transition from lizard-like hips to bird-like hips happened on one more occasion, in the ornithischian dinosaurs. (By my count, that’s as many as four distinct transitions from lizard hips to bird hips.) Or suppose the basal condition for dinosaurs was bird-like hips. In that case, you’d have an evolutionary zig-zag, with lizard-hipped dinosaurs evolving from bird-hipped ancestors, and bird-hipped birds evolving from lizard-hipped dinosaurs. Either way, there is quite a bit of explaining to do.

The New Picture

Baron, Norman, and Barrett argue that the old saurischian/ornithiscian classification gets things wrong, because it turns out that theropods are more closely related to ornithischian dinosaurs than to sauropods. They concluded this on the basis of a phylogenetic analysis of more than 400 characters, in dozens of dinosaur species from the Triassic and early Jurassic. Importantly, they looked at many characters that no one had previously fed into a phylogenetic analysis--and many details having nothing to do with the hip joint. (I am obsessing about the hip joints here, but they do not.)

The newly proposed phylogeny. Might have to rewrite all those dinosaur books.

According to this new picture, theropods and ornithischian dinosaurs together form a clade, now called the Ornithoscelida ("bird-limbed"). They keep the old name "saurischian" for the sauropods (or more precisely, the sauropodomorphs) together with another group, the herrerasaurs. [Note: this is a little confusing because, as we just saw, most theropods had lizard hips too. They now no longer count as saurischian, or "lizard-hipped"! But we shouldn't get too hung up on names. We could call the saurischians "Dino team A" and the ornithoscelidans "Dino team B" if we wanted to.]

Anyhow, the new picture suggests that the lizard-style hip construction is basal or ancestral for dinosaurs. In the early to mid-Triassic, when dinosaurs first evolved, and when the saurischians (sauropodomorphs + herrerasaurs) branched off from the ornithoscelidans (everyone else), everyone concerned had lizard hips. Then later on—possibly in the mid to late Triassic—the ornithoscelidans branched in turn into two groups. The theropods kept the ancestral lizard hips, though some of them would lose that morphology later on, when they evolved into birds, dromeosaurs, and therizinosaurs. But the ornithischians (for whom, sadly, the Triassic fossil record is pretty sparse) evolved the bird-hipped morphology pretty early on.

Some Questions About Dinosaur Hips

One striking thing about the proposed phylogenetic revision is that if we focus narrowly on the evolutionary history of one particular trait—the pelvic morphology—both the old and the new pictures provoke some of the same questions. Why, for example, did some lineages evolve the bird-hipped construction? And why did some groups, like the sauropods, retain the lizard-like construction for the long haul? Given that the hip structure changed in dromaeosaurs, why did it remain so stable in tyrannosaurs? And why do you see bird-hipped morphologies evolving from the lizard-hipped design, but (probably) not the other way around?

Some of the explanations that come readily to mind face obvious problems. For example, you might think that pelvic morphology has everything to do with locomotion. But then it’s hard to see why bipedal theropods and quadrupedal sauropods should have the same lizard-like hip morphology. Dinosaurs with a more bird-like hip construction also include both obligate quadrupeds (think of ornithischians like Stegosaurus) but also likely bipeds (maybe the dromaeosaurs, and—of course!—birds). So there just doesn’t seem to be any clear connection between this particular aspect of hip morphology and locomotion.

Another suggestion is that the bird-hipped construction, with the pubis pointing backwards, leaves more room for a larger gut. And a larger gut is a great idea for an animal that needs to digest big quantities of nutrient-poor plant material. This could well explain what was going on in the ornithischians, most of which were herbivores, as well as the therizinosaurs, which are now thought to have been an exceptional case of herbivorous theropods. But even this explanation runs into trouble: why did the ginormous sauropods retain their lizard-like hip construction? And why do you see more bird-like hips in the dromeosaurs, who were obviously carnivores?

Both the old phylogeny and the new revised one leave us with big (and as far as I know, largely unanswered) questions about why dinosaur hip morphology underwent evolutionary changes. How might scientists explore these questions further? One approach might be to study skeletal development in modern birds, so as to learn more about the developmental processes that generate the morphologies, but I'm not sure how promising that would be. If you have thoughts or speculations about how to address these questions, please feel free to share in the comments.

A Thought Experiment

There might be a further problem even with the way I've framed some of the questions above. I've been following tradition in characterizing dinosaur hip morphology as bird-like vs. lizard-like. I've also been thinking of evolutionary change as a change from one hip design to the other. But even a brief survey of the images above reveals that this is oversimplified. Dinosaur hips, including bird hips, vary in all sorts of ways. There are lots of evolutionary changes in hip structure that might not involve a shift from the lizard-like to the bird-like architecture. With that in mind, consider a thought experiment:

The Sheltered Paleontologist. Imagine a paleontologist who has somehow been sheltered from the world, and who has never had the opportunity to observe a bird or a lizard (or an alligator). But this scientist has made an extensive study, over the course of a whole career, of non-avian dinosaur hip joints. The sheltered paleontologist has studied every non-avian dinosaur hip so far extracted from the fossil record. Not only that, but the sheltered paleontologist has carefully mapped out the morphospace of non-avian dinosaur hip construction, with the aim of documenting trends and patterns in non-avian dinosaur hip evolution.

The sheltered paleontologist would not--could not--describe dinosaur hips as either bird-like or lizard-like. And so, when framing questions about the evolution of dinosaur hip morphology, the sheltered paleontologist would not fame them as I did above, as questions about the transition from a lizard-like to a bird-like design. The questions would have to be framed in some other way, relying on some other way of describing the skeletal features.

Since we can't observe dinosaurs directly, it's extraordinarily difficult for us to avoid using living organisms--birds and lizards, for example--as models for them. The thought experiment shows how this can affect even our descriptions of dinosaur morphology, and our decisions about how to individuate morphological characters. In writing this post, I actually set you up to "see" dinosaur hips a certain way, by first showing pictures of alligator and bird hips. Once you start seeing them that way, it's hard to get that distinction out of your head. But there is no reason, in principle, why anyone has to describe dinosaur hip morphology as bird-like or lizard-like.

So here's one last question about dinosaur hips: If the proposed revision to dinosaur phylogeny holds up under scrutiny, should the distinction between lizard-like hips and bird-like hips remain entrenched as a way of describing dinosaur morphology and framing evolutionary questions? If not, what should replace it?

Thanks

This post was inspired by a recent meeting of the paleontology reading group at the University of Calgary, where we discussed the new paper by Baron, Norman, and Barrett. Some of my questions about dinosaur hips are inspired by things that were said in that conversation. I'm grateful, and I hope I haven't botched anything too badly.

Reference

Baron MG, Norman DB, Barrett PM (2017), "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution," Nature 543: 501-506.