* Alison Laurence is a cultural historian who writes about extinct animals, museum display, deep time, and de-extinction. She is an adjunct lecturer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and an editor for Contingent Magazine (a non-profit publication whose writers are non-tenured/TT historians). She writes…

In early April, 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced that it had carried out “the world’s first de-extinction” via genetic engineering.[1] By sequencing the dire wolf genome, modifying a handful of genes in cloned gray wolf cells, and gestating the engineered embryos in domestic dogs, the venture-capital backed company created three living, breathing, howling creatures that they called dire wolves.

A chorus of scientists, conservationists, historians, and philosophers (among others) swiftly contested Colossal’s claim.[2] The institutional authority on dire wolves, the La Brea Tar Pits & Museum in Los Angeles, weighed in too. Over 4,000 dire wolves have been excavated from the tar pits. These canids are the most common mammal found in this particular fossil record, the most extensive and best preserved Pleistocene locality on the planet.[3] “Sorry, they’re totally still extinct,” the museum says of the dire wolf, which died out around 13,000 years ago along with other Ice Age animals that struggled to adapt to a changing climate and, perhaps, new pressures created by growing human populations.[4]

If you want to see uncontested, albeit fossilized, dire wolves, take a trip to the Tar Pits museum. Bask in the orange Dayglo display that illuminates over 400 Aenocyon dirus skulls. It’s a reverent and photogenic installation that welcomes reflection on worlds lost. Pay your respects to the dire wolf endling (a partial specimen, just a jaw bone). Notice the accompanying sign, which announces it as the “LAST KNOWN REAL DIRE WOLF IN THE WORLD!!”[5]

Dayglo Dire Wolves at the Tar Pits Museum. Photograph by author, November 10, 2016

And if you make your pilgrimage to the dire wolves by September 15, 2025, spend some time in the museum’s temporary exhibit Excavations, created by contemporary multimedia artist Mark Dion.

Excavations describes itself as a “mischievous installation” that “uses art to challenge the way we display scientific information.”[6] This is in keeping with Dion’s often playful, always critical interventions into the history of natural history. Dion’s installations challenge people to regard nature— and particularly how institutions study, collect, and display that nature— aslant. Works such as “Library for the Birds of Massachusetts” and “Tar and Feathers” ask viewers to consider the conditions that cultivate liveliness and those that result in the death of the animals put on display.

Dion has previously tackled the display of extinct animals, too. In Toys ’R’ U.S. (When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth), first exhibited in the immediate wake of Jurassic Park, dinosaurs have taken over an imagined child’s bedroom. There’s the Flintstones’ purple pet Dino on a pillow and more scientifically informed representations on posters. Toys, plastic and plush, are scattered about the place on books, bedspread, board games, backpack. Toys ’R’ U.S. calls attention to interconnections between natural history and popular culture by illustrating the prevalence of dinosaurs in and as American consumer culture.

Toys ’R’ U.S. (When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth) was originally exhibited in 1994 and is seen here in 2017,in the survey show Mark Dion: Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. Photograph by author, December 16, 2017

I will come back to Dion’s work at La Brea at the end of this essay. My angle isn’t critique; instead, I am interested in contextualizing Dion’s “mischievous installation” within a longer history of troubling and troublesome displays at the tar pits.

* * *

Creatures living in the Los Angeles Basin have been getting into trouble with the “tar” for many millennia. The still-active asphalt seeps, located in what is now a busy commercial district of Los Angeles, have entrapped plants, animals, and the very occasional human going on 50,000 years. La Brea contains the remains of extinct icons of the Ice Age as well as plants and animals that remain extant. It is also a public park. Some people visit to admire the excavations, others just need a place to walk their dogs.

The park has been open for just over a century. Its public nature was a requirement stipulated by the site’s previous owner, oilman G. Allen Hancock, when he handed over the deed to Los Angeles County. While the park is free, the museum that opened on site in 1977 charges an entrance fee. Both the museum and the grounds are on the verge of a major transformation, which includes the addition of a new fossil lab, outdoor classrooms, and expanded green space for public recreation.

The asphalt of La Brea is an unruly agent that resists passive exhibition. The viscous substance seeps up throughout the park, unsanctioned, and sticks to visitors’ shoes. The malodorous methane, which is what causes the asphalt to bubble, creates a less-than-pleasant sensory experience for some. (Personally, I love it.) And the fenced off pits continue to collect future fossils, including trash that visitors have tossed over the fences as well as hapless urban wildlife that gets entrapped.

I’ve written elsewhere about temporal reorientation at the tar pits. The free outdoor displays can help visitors experience time out of order, challenge people to see themselves as part of an ecological continuum, as heirs and ancestors all at once. This is important, because as geoscientist Marcia Bjornerud has argued, humans struggle to keep (deep) time. Being “time illiterate,” unable to think far into the planet’s past or future, stands in the way of collectively acting to ameliorate the ongoing climate crisis.[7] Encounters with the asphalt, though, may help visitors to develop some deep time literacy. A visit to see the seeps is what anthropologist Vincent Ialenti might call a “reckoning,” an exercise that trains people to be sensitive to time scales that we cannot experience for ourselves.[8]

Permit me to quote myself:

La Brea has the potential to offer visitors a new temporal perspective wherein past and present are not distinct but proximate, imbricated, in relation. If we take our cues from the tar itself, linear time fades away and the years start to stick together. Creatures that never could have met in life share space in the multispecies matrix of a tar pit, for the methane that still causes the asphalt to ooze and bubble has ‘churn[ed] the bones from different animals and time periods into complex jumbles.’ The communal grave known as Pit 61/67 (signifying that these were the 61st and 67th of 96 exploratory excavations dug during the 1910s) contained the bones of dire wolves that lived 13,000 years ago as well as those of a domesticated dog that barked 6,000 years later. What’s more, as informational placards throughout the park explain, physical proximity does not correlate to temporal proximity. Excavators unearthed a juniper tree in Pit 3 that last bloomed 17,000 years ago. Digging just feet away in Pit 4, they found the bones of sabre-tooths twice as old.[9]

Put another way, the asphalt troubles time, disturbing and disrupting familiar, shallow, human historical chronologies. It causes other kinds of trouble too, for those animals that get mired and for those visitors who find the exhibition of entrapment (whether intentional or incidental) distressing, which I will illustrate with some examples from the archives.

“Trouble,” of late, is an oft-used word within the environmental humanities and science studies. For Donna Haraway, “staying with the trouble” of today means focusing on our present multispecies mortal mess rather than attempting to make “an imagined future safe.”[10] There is another lineage I’m drawing on as well. The late Civil Rights activist and U.S. Representative for Georgia, John R. Lewis, charged people to get into “good trouble.” When systems are unjust, it is the citizen’s responsibility to challenge— to trouble— them. (Perhaps it’s worth noting that I’m currently affiliated with John R. Lewis College at the University of California, Santa Cruz.) Lewis’s instruction reminds us that trouble is relative, neither good nor bad in itself. To trouble, then, is to consider other possible presents. Trouble seeds the conditions of critical consciousness. Being troubled, making trouble, is an uncomfortable and urgent state of possibility.[11]

* * *

It’s the winter of 2022. The weather is cool and the asphalt isn’t particularly tacky today. The placard on Pit 13 that warns visitors to “tread lightly” isn’t startling on a day such as this. Still, the sign inures visitors to the unpleasant reality that they might spot some birds or small mammals entrapped, exhausting themselves as they try to get free, expiring from the effort.

“Tread lightly” at La Brea. Photograph by author, December 26, 2022

It’s the summer of 1958, a warm July day. The on-site tar pits museum doesn’t exist yet but the public park itself is something of a museum, managed by what was then called the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art. There are statues of Pleistocene animals scattered about and an observation pit that allows visitors to look down into a staged excavation site. There’s also a guide who lives on site. Hired chiefly to protect the county’s property, the guard took on interpretive duties as well.

Two mockingbirds have found themselves mired in one of the asphalt seeps. La Brea’s lush parkland, with native and introduced botanicals, is inviting for birds, pollinators, and other critters seeking food and shelter in the midst of L.A.’s concrete jungle. It could be that the songbirds tried to bathe in the asphalt, as water sometimes collects on its surface. So there the birds were, stuck fast, “entrapped and gaping without a sound.” The scene alarmed visitors, one Ethel Hendrickson in particular. She asked La Brea’s resident guard-guide for help, but he told her not to worry, that this kind of thing was a “daily” occurrence. Outraged, Hendrickson wrote to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors: “we are civilized, and as such, the proper care of wild life, particularly in our public parks, [is] our responsibility.” She asked the county to put nets over the tar pits and install dedicated bird baths throughout the park. The supervisors instructed museum leadership to “give thought” to Hendrickson’s request. Perhaps they did, but they did not acquiesce.[12]

Despite the nonchalance that troubled Hendrickson, guards and the general public did mount rescue efforts for entrapped animals, especially for dogs and for the occasional human who got into trouble in the tar pits. The accidental entrapment of people and their companion animals was checked when the county installed fences around the pits in 1948, though that couldn’t keep out winged things or animals small enough to scamper through or over the chain link. In 1997, a visitor climbed over the fence of Pit 9 to rescue what he recognized as a then-endangered peregrine falcon. He got the bird out but it succumbed to the encounter anyway. To the relief of conservationists (but of no comfort to the expired animal) it turned out to be a common Cooper’s Hawk.[13]

The museum’s decision not to make the pits safe for all animals was likely rooted in economics. Incidentally, though, these troubling encounters with the asphalt are instructive, for those who notice them. La Brea bears witness to life and loss. As extinction studies scholars argue, “staying with the lives and deaths of particular, precious beings” is prerequisite for generating knowledge and energy to contest extinction as well as “new modes of survival and fragile flourishing.”[14]

The fence suggests that visitors are safe from the mammoth’s fate; other interpretive materials indicate otherwise. Photograph by author, December 21, 2020

It’s June 1968 and there’s still no on-site museum. Visitors must travel miles across town (to what has been renamed the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County) to see fossils from the tar pits on display. But there is a new outdoor exhibit at La Brea, a Pleistocene Zoo. The most affecting of these displays is the tragic mammoth family. A female Imperial mammoth has found herself stuck fast. She trumpets (silently, eternally) to her mate and her calf who stand safe on the shore of the lake pit.

Virginia M. Humphreys is troubled by this scene. “I spent a lot of time in this park as a child,” she wrote to the Los Angeles Times, “and I recall the mere thought of anything drowning in the tar upset me. Now children can see, in living color, what this pitiful scene must have been like. I believe it should be removed, or at least modified.”[15] The unease that Humphreys described is the precise aim of this scene, which sought to bring the prehistoric past into the present by way of emotions.[16] Affect, it turns out, is an effective way to motivate people to be more conscious and active environmental stewards.[17]

The mammoth has become a beloved neighbor, known to generations, and many visitors reflect on it as an important artifact. “As a 7-year-old when I visited the place back in the ’80s, the Mammoth sculptures connected me to the past in an emotional way,” one Angeleno told the Times recently. “You kind of got how it was an important place even before you understood the science and history behind it. I think the mammoth scene in the tar pit is important to captivate the younger kids...”[18]

Be sure to look out and look down at La Brea. Photograph by author, December 26, 2022

Captivation is critical and, at La Brea, sometimes literal. Recall that placard on Pit 13 that calls on visitors to “tread lightly.” It further warns those who take the time to read the smaller print that the asphalt seeps “could take you down too, if you’re not careful.” Traffic cones through the park direct visitors around asphalt that has broken out of its enclosure. “LOOK OUT” a neon cone counsels, but the arrow on that cone points down into the collective grave that has been entombing animals for tens of thousands of years.

The cones aren’t intended to cause alarm. Others are emblazoned with more humorous language: “GOOEY,” for example, and “SMELLY.” They are a lighthearted and pragmatic embrace of the asphalt’s unruliness. This is also an interpretive choice that (along with language such as that on Pit 13) asks visitors to see themselves akin to animals that have lived and died at La Brea over millennia. Humans are vulnerable too, these displays remind, troubling a popular tendency to draw distinctions between people and other animals.[19]

* * *

It’s a Monday in September, 2024, and I arrive at the Tar Pits Museum upon opening, when it won’t yet be busy with school groups or tourists. I pass the Tar Pull, where visitors test their strength against the asphalt’s suction, the sturdy mastodon skeletons, the Instagrammable wall of dire wolf skulls, the fossil lab. At the end of my loop, I come to Excavations. This temporary exhibit was the result of Mark Dion’s extended residency at La Brea, funded by PST ART: Art & Science Collide, a Getty scheme that funds projects across Los Angeles. The show is compact, featuring four distinct displays that don’t seem out of place in a natural history museum—the visual language conforms to the other exhibits in the building—until one takes a closer look.

A giant pack rat guards its nest in Mark Dion’s Excavations. Photograph by author, September 23, 2024

There’s a skeleton that seems not unlike others in the museum, but this one turns out to be supersized, a scaled up pack rat that glows under black light. It stands atop a nest of tools and trash. This hypothetical animal has been excavated and re-articulated into a world that is filthy with material culture. Nearby a busy-but-well-kept workstation draws attention to the labor and the artfulness of science (as so much of Dion’s work does). There’s thrift on display too— a tin of Planter’s nuts has been repurposed to hold drill bits, tools are stored in an empty can of coconut cream.

Art & science in the works in Mark Dion’s Excavations. Photograph by author, September 23, 2024

There’s another cordoned off display that mediates the viewer’s experience twice over: traffic cones are part of the exhibit, but are the museum’s ropes? It’s a three-dimensional snapshot of a snapshot that captures a staged moment of demolition wherein drywall is pulled away to reveal a curious diorama. Instead of the taxidermy that is typical of a natural history museum habitat group, the animals are skeletal. They are, however, depicted in a vital moment. A bird of prey is perched in a tree and holds tight to its next meal (though time has already picked clean the bones). It menaces with wings outstretched to warn off the hungry beast below.

Bursting the limits of time (and drywall) in Mark Dion’s Excavations. Photographs by author, September 23, 2024

It’s hard to see the whole scene. The visitor can’t get near enough because of the stanchions, a frustrating barrier that enhances the diorama’s effect. Though scientists and artists do their careful work, the prehistoric past is ever at a distance. Those beings that have gone extinct are gone forever. Dion’s interpretation of an extinct animal diorama acknowledges this by refusing the viewer a satisfying look.

Which brings us back to the dire wolves.

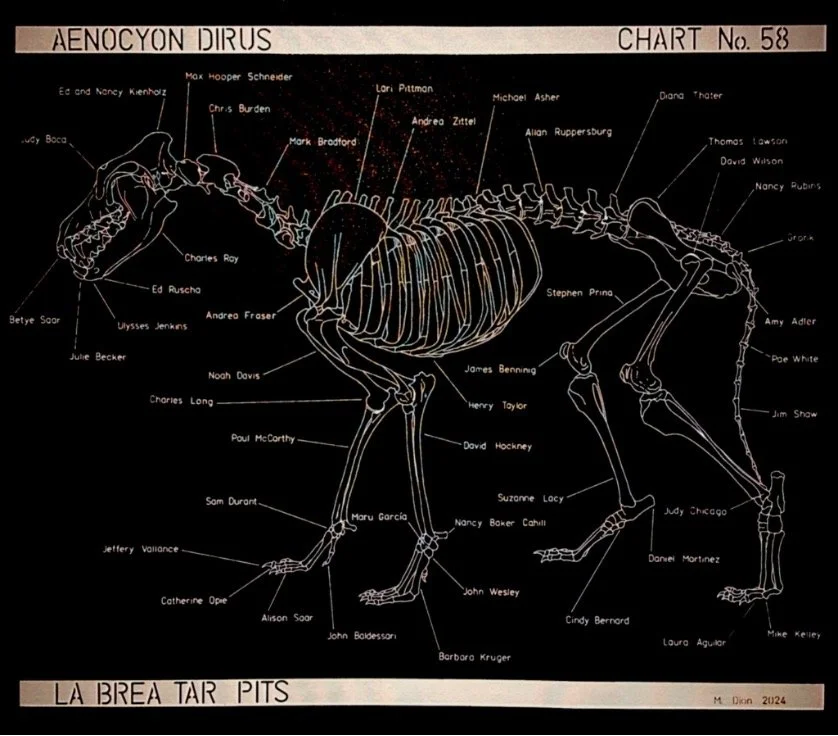

The final component of Excavations is a playful twist on the anatomical chart. Skeletal drawings of extinct species line the walls of the space. Where one would expect to find the names of bones, Dion has mapped out other relations. The body of Equus occidentalis, a horse that evolved and went extinct in North America, plots out neighborhoods and landmarks of Los Angeles. Mammuthus columbi maps paleontological professionals (some well known, others less so; some living, others long dead).

Dion’s Aenocyon dirus, his dire wolf, charts contemporary visual artists with links to Los Angeles. Those who are named use their painting, photography, sculpture, performance art, biotic experimentation, classroom practice, and other forms of creative intervention, to speak on social and environmental issues that are both enduring and…one is tempted to say… dire.

An artful diagram of Aenocyon dirus in Mark Dion’s Excavations. Photograph by author, September 23, 2024

It’s a mischievous coincidence that Dion’s dire wolf, in particular, is the species that happens to conjure the artistic eye. It’s this critical perspective (shouldered, too, by scholars in the humanities and social sciences!) that is so urgent in this new era of “de-extinction,” when the mere existence of fluffy GMOs called dire wolves allows legislators to justify the removal of currently threatened species from Endangered Species Act protection.[20]

By challenging what people expect to see in a natural history museum and reinterpreting inherited forms of display, Excavations fits comfortably within La Brea’s lineage of troubling exhibits. Mark Dion’s temporary show is on view through September 15, 2025. La Brea’s “REAL” dire wolves, having endured already for many thousands of years, will stay on display for generations to come.

Notes

[1] The claim is too broad. It ignores the short-lived de-extinction of the Capra pyrenaica subspecies in 2003. We mustn’t forget Celia, the cloned Pyrenean ibex (otherwise known as a bucardo) who lived for several minutes before expiring due to a malformed lung, the first (sub)species to go extinct twice. The novelty of the so-called dire wolf is that it was “resurrected” from ancient DNA. On the bucardo, see Lydia Pyne, Endlings: Fables for the Anthropocene (University of Minnesota Press, 2022), 31-39, and Adam Searle, “Spectral Ecologies: De/extinction in the Pyrenees,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47, no. 1 (March 2022), 167-183. Note that because the bucardo clone did not survive, Searle describes the de-extinction as a “failed” effort.

[2] See for instance the recent Daily Nous roundtable. For critiques from within the conservation community, see IUCN Species Survival Commission Canid Specialist Group Taxonomic Review Task Force, “Conservation Perspectives on Gene Editing in Wild Canids,” April 18, 2025.

[3] Some notes on language: “La Brea Tar Pits” is a redundant phrase, la brea being the Spanish for “the tar”; “Tar Pit” is the colloquial name for what are, in actuality, asphalt seeps. The deep pits seen today are not ancient, but relics of asphalt mining and fossil excavations.

[4] “Dire Wolves: Sorry, They’re Totally Still Extinct,” La Brea Tar Pits & Museum, April 16, 2025.

[5] Riley Black, “La Brea Telling the Truth,” Bluesky, June 22, 2025. The endling display pre-dated the dire wolf announcement, but I believe the accompanying sign has been updated, the bold declaration of reality added in response to Colossal’s announcement. Other similar signs in the museum’s fossil lab do not emphasize authenticity.

[6] “Mark Dion: Excavations,” La Brea Tar Pits & Museum.

[7] Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Princeton University Press, 2018), 7.

[8] Vincent Ialenti, Deep Time Reckoning: How Future Thinking Can Help Earth Now (MIT Press, 2020).

[9] Alison Laurence, “Out of Time at the La Brea Tar Pits: People and Other Animals in a Time Capsule of Ice Age Los Angeles,” Museum & Society 20, no. 1 (July 2022), 76-7. Quotes and information sourced from placards on Pits 3, 4, and 61/67.

[10] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2018), 1.

[11] There’s a third sense that belongs in the footnotes. Trouble was the name of my childhood Cairn Terrier. He was not dusky like Toto (the breed’s most famous representative) but a sweet wheaten terror. He had the name already when we adopted him from the shelter; it suited him.

[12] Ethel M. Hendrickson to Board of Supervisors re: entrapped birds, July 3, 1958. Folder: Bird in Pit. Hancock Park File Cabinet. Museum Archives. NHMLA Archives.

[13] “Woman Nearly Loses Her Life Saving Dog from La Brea Pit,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1937; “Little Girls and Dog Saved from Tar Pit,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1943; “Dog Walks with Ghosts of Giants before Tar Pits Take Life Toll,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1951; Bob Pool, “Plight of Bird Stuck in Tar Pit Brings Flock of Rescuers,” Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1997. On the addition of fences, see Cathy McNassor, Los Angeles’s La Brea Tar Pits and Hancock Park (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing), 67.

[14] Deborah Bird Rose, Thom van Dooren, T. and Matthew Chrulew, eds., Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death, and Generations (Columbia University Press, 2017), 8. Perhaps I should clarify that La Brea is not a cause of Pleistocene extinctions, merely a fossil record that records creatures now extinct.

[15] Virginia M. Humphreys, “Tar Pits Statue Rapped,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1968; Ken Reich, “In Ferocious Fiberglass: Tar Pits Mammoth Delivered,” Los Angeles Times, 19 January 19, 1967;“First of 52 ‘Beasts’ Put in La Brea Pit,” Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1968; Eric Scott, “They Live Again: Sixty Years of Sculpture in Hancock Park,” Terra 24, no. 1 (1985), 23-30.

[16] The museum’s own scientists struggled to accept the sensationalized nature of the mammoth scene. The lake pit didn’t exist during the Pleistocene, it’s a relic of nineteenth-century asphalt mining. This is not at all a representative entrapment scenario. See William Akersten to Dr. Mead and Mr. Arnold, Memo re: Lake Pit entrapment diorama, May 8, 1975. Folder: Hancock Park Development 1970s. Box: Hancock Park. NHM, Museum Archives. For a “gentle polemic” on La Brea’s sensationalism and its connection to oil culture, see Stephanie Le Menager, “Fossil, Fuel: Manifesto for the Post-Oil Museum,” Journal of American Studies 46, no. 2 (May 2012), 378.

[17] For instance, Audrey Bryan, “Affective Pedagogies: Foregrounding Emotion in Climate Change Education,” Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review 30 (2020), 8-30. For more environmental humanistic treatments of emotions and conservation, see Dolly Jørgensen, Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age: Histories of Longing and Belonging (The MIT Press, 2019); Jamie Lorimer, Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature (University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Ursula K. Heise, Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species, Chicago: (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

[18] Dorany Pineda, “Mammoth Memories,” Los Angeles Times, 27 August 27, 2019.

[19] Ross J. Wilson, “Encountering Dinosaurs: Public History and Environmental Heritage,” The Public Historian, 42, no. 4 (November 2020), 121-36. I am ever grateful to Harriet Ritvo for this language.

[20] Chris D’Angelo, Roque Planas, and Jimmy Tobias, “Trump's Interior Secretary Has Close Ties To The De-Extinction Company He Promotes,” Public Domain, May 3, 2025, https://www.publicdomain.media/p/interior-doug-burgum-colossal-biosciences-deextinction