Derek Turner writes . . .

Paleontology and geology have a long and complicated relationship with fossil fuel extraction. This goes way back to the early nineteenth century, when the industrial revolution in Britain had increased demand for coal, leading to a spike of interest in stratigraphy. More recently, the oil industry has provided crucial data. For example, petroleum geologists working for Mexico’s national oil company, Pemex, are the ones who discovered the Chicxulub crater in the late 1970s. The oil industry geologists were doing aerial magnetic surveys of the Gulf of Mexico while looking for promising places to drill.

I hope that someone, someday, will tell the story of paleontology’s relationship with the oil industry in all the detail it deserves. Here I’m just going to follow one thread of that larger story. I’m not a historian, and so my “research” is limited to some online sleuthing and assembling of factoids.

This particular narrative thread concerns the Sinclair Oil company’s efforts to cash in on dinosaurs. Along the way, the company funded paleontological research, fueled public interest in dinosaurs, and perhaps even found a way to co-opt a children’s book that explicitly criticizes the commercialization of dinosaurs.

Oliver Butterworth’s The Enormous Egg (1956), was one of my favorite books when I was a kid. My first-grade teacher, Miss Hagen, helped me find it in the school library. The book has a fascinating connection to the Sinclair Oil story, but let’s start at the beginning.

1932 | The Logo

Sinclair Oil company registered its trademark green sauropod in 1932. We don’t have many Sinclair gas stations here in the northeast, but the green Brontosaurus named "Dino" is a familiar sight in parts of the western US.

Originally founded in 1916 by Harry Sinclair, the Sinclair Oil Corporation was right at the center of the Teapot Dome scandal in the 1920s, which involved some shady oil leases on federal lands in Wyoming. As part of the fallout from that scandal, Sinclair would eventually serve time in prison for tampering with a jury. By the early 1930s, he was back at the helm of the company he founded, and set out to rehabilitate its tarnished reputation—with the help of dinosaurs.

1934 | The Chicago World’s Fair

How interesting that the dinosaurs are fighting. Also note the prominent placement of the Sinclair sauropod in the background.

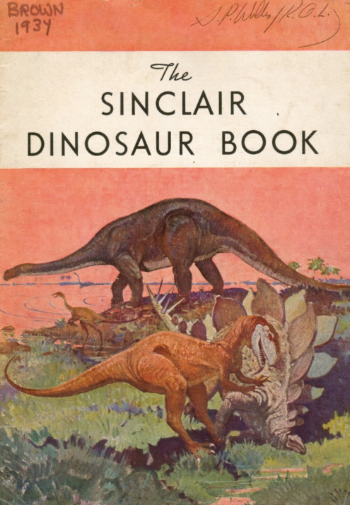

Sinclair paid for an exhibit at the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair. The exhibit was basically just a giant papier-mâché sauropod—a huge model of the company’s new logo! For this exhibit, they needed paleontological expertise, and so the company brought in the renowned fossil collector Barnum Brown. Brown himself wrote the brochure for the World’s Fair Exhibit that was published as The Sinclair Dinosaur Book. During the 1934 field season, Sinclair Oil funded Brown’s fieldwork in Wyoming, where the paleontologist was working a sauropod quarry, of course.

1938 | Texas Sauropod Tracks

Sinclair Oil would continue to fund important paleontological fieldwork, especially work that had some connection to sauropods. In 1938, Roland T. Bird, working for the American Museum of Natural History, found his way to the Paluxy River in Texas, where locals had already taken notice of the dinosaur tracks. Bird would go on to publish the first scientific descriptions of the sauropod (we now think probably titanosaur) tracks. (Here is a great example of his writing about the tracks.) His subsequent field season, in the summer of 1940, was paid for in part by—you guessed it—Sinclair. With funding from big oil, Bird excavated huge slabs of rock containing sauropod tracks and had them shipped back to the American Museum of Natural History, in New York City.

1956 | “Only living dinosaur in the world”

In The Enormous Egg, Uncle Beazley is a Triceratops who mysteriously hatches in a New Hampshire chicken coop. A kid named Nate takes care of Uncle Beazley with the help of a friendly local paleontologist, Dr. Ziemer. But because New Hampshire winters are so cold, and Uncle Beazley is eating all the neighbor’s flowers, they haul the poor dinosaur down to Washington, DC, where after various mishaps, he ends up living at the National Zoo.

The book mixes paleontology with political satire. The story begins in the town of Freedom, NH. Because where else would a dinosaur hatch? The “bad guys” in the story are the US senators who do not want to allocate funds for dinosaur food. After all, says Senator Granderson, dinosaurs don’t come from America. Leave it to politicians to get the empirical facts wrong while making ethically questionable arguments. But Nate and the paleontologists organize pro-dinosaur protests, as well as a letter-writing campaign, and the senators cave under pressure.

Along the way, Nate also rejects various proposals for cashing in on the dinosaur. Amusingly, one person wants to use Uncle Beazley to help market his brand of whiskey! But the most astonishing passage in the book is this:

The man nodded. "My name's Bill Griner. I got a gas station up to Conway, and I heard about this dinosaur you got down here. I got to thinking that would be a swell thing to have in a cage at my gas station. The stations are all doing that now--they got bears, or a raccoon, or maybe a monkey. It's good for business. People stop and buy gas at a place that's got animals. Now if I had a dinosaur up there, I'd put up a big sign -- 'Only living dinosaur in the world' -- and just about everybody would stop to see it, and buy gas. See what I mean? (p. 99).

Nate, of course, tells the huckster to take a hike. This sure looks like a not-so-subtle jab at a particular oil company.

1964 | Dinoland

Just a few years after the publication of Oliver Butterworth’s children’s book, Sinclair Oil was back at the World’s Fair, this time in New York with a major exhibit called “Dinoland.” Dinoland featured “nine life-sized prehistoric monsters” made out of fiberglass. (Here are some interesting reminiscences.) Some important paleontologists, including John Ostrom, Edwin Colbert, and even Barnum Brown (who was then in his late 80s), were brought in as consultants. The whole thing was a thinly veiled marketing ploy. Visitors to Dinoland received coupons for a free gallon of gas at their local Sinclair station. There was also a futuristic vending machine that would make a plastic dinosaur toy for kids on the spot. Tourists could buy postcards that happened to have the Sinclair logo in one corner, which included the distinctive green Brontosaurus.

51 million people attended the 1964 New York World’s Fair. For comparison, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, only had 7.1 million visitors in 2016.

After that, the Dinoland Dinosaurs went on the road, appearing in various cities, where many more people got to see them.

1967 | Uncle Beazley at the Smithsonian

One of those “Dinoland” dinosaurs was a Triceratops. Eventually Sinclair would donate the “Dinoland” sculptures to various places. For example, the iconic fiberglass sauropod now lives (appropriately) at Dinosaur Valley State Park in Texas, near the Paluxy River, where Roland Bird had studied the sauropod tracks. If you ask me, New York, which had already received some real sauropod tracks from Texas, got the better end of that deal.

Perhaps inspired by Oliver Butterworth’s book, somebody had the idea of donating the Triceratops to the Smithsonian.

To start with, the Triceratops lived at the National Zoo. Then in 1967, the sculpture was even used in a children’s TV production of The Enormous Egg that aired on NBC. At least since then, the sculpture has been known as “Uncle Beazley.”

Uncle Beazley subsequently migrated around the Washington, DC area. He resided for a while at a museum in Anacostia, but then relocated to the National Mall, where he stood outside the National Museum of Natural History well into the 1990s. Uncle Beazley has since found his way back to the National Zoo. I haven’t (yet) seen him there, but apparently he is close to the lemurs.

Oliver Butterworth lived until 1990. I have to wonder what he made of the fact that the oil company that he was surely criticizing in his book ended up supplying the sculpture that gazillions of visitors to the Smithsonian and the National Zoo would know as “Uncle Beazley.”

Some Themes

You’ve got a big oil company paying for some notable paleontological research on the animal that it adopted as its logo.

You’ve got public spectacle, designed with the help of leading paleontologists, paid for by big oil, that mixes marketing and science education.

You’ve got an adorable children’s book that sharply criticizes the commercialization of dinosaurs. But through a bizarre twist of fate, the book’s main character lives on as a memento of an oil company’s effort to do the very thing the book was criticizing.

I don't want to make too much of this one narrative thread. But it does point to some historical mutual dependencies between paleontology and the oil industry. There would appear to be some connection between our love of dinosaurs and our civilization’s darker, unsustainable addiction. Uncle Beazley is the poster hatchling for this complicated history.

Recommended Reading

Oliver Butterworth, The Enormous Egg, Illustrated by Louis Darling. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company, 1956.