Derek Turner writes . . .

What if our representations of dinosaurs sometimes say more about us than about the animals themselves?

Why, for example, do we so frequently represent dinosaurs as fighting? One classic example of this is Charles Knight’s famous painting of the gladiatorial face-off between Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex.

T. rex couldn’t really box, but look at how the animals are squaring off like prizefighters on opposite sides of the ring. Or like cowboys facing off at high noon. We’re looking at dinosaurs, but the ritual being enacted here is familiar. And human. I observed many fights when I was in junior high school, and every single one of them started with a ritualized face-off, just like this. Or like this:

The trouble (as Brian Switek explains here), is that there is not a shred of evidence that such duels ever actually happened. That bears repeating: THERE IS NO EVIDENCE THAT TRICERATOPS EVER ENGAGED IN COMBAT WITH T. REX. There are a few suggestive tooth marks in Ceratopsian frills, but toothmarks do not necessarily imply combat, since they could easily have been made post-mortem.

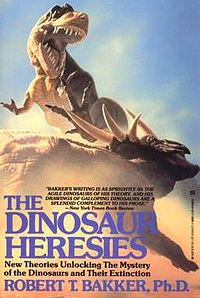

None of this is to say that representations of T. rex fighting Triceratops are inaccurate. The point is that such representations are only loosely constrained by the empirical evidence. Even as our understanding of dinosaurs has changed a great deal, certain ways of representing them have remained deeply entrenched. For example, this was the cover of a book that was one of my own favorites, when I was a kid:

But even as scientists like Robert Bakker led the dinosaur renaissance in the 1980s, the dueling dinosaur motif persisted.

Seen in historical context, there is nothing terribly heretical about the depiction of dinosaurs fighting.

Prehistory as a Mirror for Humanity

The evidential slack means that that there is room for us to read our own human foibles and predilections back into nature. We reconstruct prehistoric life—and dinosaurs in particular—in our own violent image.

In an earlier post, I suggested that part of what draws us back to the Mesozoic is nostalgia for a wilder world where humans have no place. But we also populate that wilder world with animals that can seem a lot like us, animals that wasted their time on Earth in perpetual conflict and combat. My claim is that representations of prehistoric life can function as a mirror that shows us something about ourselves, if obscurely.

Recently on a visit to Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, I saw a (quite famous) dinosaur skeleton that, amazingly, drove both of these points home at the same time. It was Deinonychus—a specimen that, interpreted by John Ostrom, helped to launch the dinosaur renaissance. But there's poetry in the decisions about how to mount the skeleton:

The animal is pouncing, in the middle of an attack. The dynamic pose contrasts with earlier representations of dinosaurs as sluggish, such as Knight’s painting. But combat is the common thread. Why not portray Deinonychus as sitting, or napping? Many predators spend most of their time lazing around. One part of the answer is that we like to watch violence. Another part of the answer is that we like being told that our own violent tendencies are natural.

What is Deinonychus pouncing on? You! The museumgoer. Even though it’s just a skeleton suspended from the ceiling, the museum exhibit places you, the visitor, in the wilderness before time, where animals like Deinonychus might leap at you and eat you. The exhibit places you in a fight with a dinosaur, and one that you are guaranteed to lose. There is a fascinating double movement here: the exhibit cuts humanity down to size, but the animal doing the slashing is strangely humanized. It is using its weapons to attack you in the way another person might do.

Dinosaur Weaponology

This obsession with dinosaur fighting also, I suggest, has some impact on paleontological research. A lot of work goes into the functional morphology of dinosaur weapons. Consider the thick cranial domes of some pachycephalosaurs. In the dinosaur books I loved as a kid, the animals were often portrayed like this:

These, presumably, are males, ramming each other into submission to see who gets the territory, or the females. The thick skulls evolved by sexual selection. Or so the story goes.

Along the way, however, some scientists have expressed skepticism about this picture. For example, Kenneth Carpenter argued (here) that the tops of pachycephalosaur skulls have too little contact area for the head butting to work. Instead, he hypothesized that the animals must have engaged in "flank butting." Others have wondered about the morphology of pachycephalosaur necks. Was the curvature of the neck vertebrae well designed for withstanding impacts? Perhaps the skulls were instead used for display or recognition. Meanwhile, other researchers have looked at pathologies--at the frequency of bone lesions in pachycephalosaur skulls--and argued that those are suggestive of injuries due to head-butting. Debates about the head-butting hypothesis have also gotten plenty of public attention.

My worry about all this is not that the head-butting hypothesis is wrong. My worry is just that there is so much attention lavished on research on dinosaur weapons--and on what are thought to have been male weapons, at that. There are lots of interesting questions that could be asked about pachycephalosaurs--about their ecology, about other aspects of their behavior--and yet it almost seems like the only thing we see when we look at the animals are their weapons. When dinosaur weaponology research gets disproportionate public attention, that creates the impression that the weapons were their most important features. Indeed, we often treat dinosaurs' weapons and armor as their defining features. But there's no deep reason why we have to do that.

Stereotypes about Dinosaurs?

We also represent dinosaurs in a way that showcases their weapons. If you take time to observe carnivores—your pet dog counts, as do the backyard coyotes—you might notice that they do not spend much time with their mouths hanging open. If we wanted to, we could adopt a practice of always portraying dogs like this:

But this would be a kind of reputational injustice to dogs. The representation isn’t exactly wrong—dogs do sometimes act like this—but it’s biased. Just try, however, to find a museum exhibit in which a carnivorous dinosaur is reconstructed with its mouth closed.

There are interesting cases where people have messed up stereotypes about other animals. (Actually, these can interact in complex ways with stereotypes about people. These are complicated issues, but this book by Vicki Hearne might be one place to start exploring them.) For example, many people think of pit bulls as especially ferocious and aggressive dogs. But people who’ve hung out with snuggly, well cared for pit bulls know otherwise. It's not even entirely clear what breed, if any, the term "pit bull" is supposed to pick out. They are just dogs. Perhaps we are guilty of stereotyping dinosaurs in somewhat the same way.

From the War of Nature

This tendency to read of our own interests and predilections back into nature is nothing new. Darwin did the same thing. Many people have cited the famous closing sentence of the Origin of Species, the one that opens with, “There is a grandeur in this view of life . . .” For many years, Stephen Jay Gould wrote essays for Natural History magazine under the heading, “This View of Life.” However, the sentence that precedes the famous closing line is just as revealing--and, I would argue, kind of problematic. Here it is:

“Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows”

(p. 425. All page numbers are from this version of the Origin, which is available online.)

Nor is this the only place where Darwin uses war and battle as metaphors. In his chapter on the struggle for existence, he writes that “battle within battle must ever be recurring with varying success . . .” (p. 71). In the discussion of sexual selection, he refers to “the law of battle,” according to which males of most species must use their “weapons” to fight for access to females (p. 84). Remember the pachycephalosaurs.

Just to be clear: there is absolutely nothing in the theory of natural selection that obligates us to think of it as involving war, or combat, or fighting. In familiar schematic form, all you need for natural selection is heritable variation in a population that makes some difference to survival or reproductive success. Darwin’s line about the “war of nature” is gratuitous. So why is it there? Of course predation is violent. But war and battle are, in the first instance, human activities. These metaphors are optional.

Darwin’s penultimate line looks a lot like theodicy. The war of nature is horrible and gruesome, but maybe it’s justified by its results—the “most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving.” Of course, that most exalted object is us. So our own human activity—war—is made to seem natural, because that’s what all other creatures have been doing all along anyway. But the war of nature is then supposed to be justified by the fact that it has produced “higher animals” like us that make war with each other.

It’s hard to see the grandeur in this view of things.

Further Reading

This post builds on some ideas about war as a metaphor that I developed in an earlier paper. There may also be a connection between seeing nature as a scene of constant warfare, and seeing ourselves as being at war with nature.